- If I ruled the world

- I’d free all my sons

- Black diamonds and pearls

- If I ruled the world

- And then we’ll walk right up to the sun

- Hand in hand

- We’ll walk right up to the sun

- We won’t land

- We’ll walk right

- up to the sun

- Hand in hand

- We’ll walk right up to the sun

- We Won't land...

- Nas (Featuring Lauryn Hill), If I Ruled the World

I'm never ready to return to the United States.

I never am after traveling to Africa, especially with students and what Baba Ayi Kwei Armah would call the "companions" of common purpose.

I never am when reflecting on the fact that our best thinkers have increasingly been siphoned off to the intellectual and cultural cul-de-sac of explaining our African humanity to societies set up on the premise that we lacked humanity. That our best thinkers have increasingly been trained, especially after desegregation, to create brilliant analyses of "blackness" that empty into individual praise and advancement, leaving more and more of their kindred to suffer unchanging oppression.

We prepare to return to America tomorrow, to a country run by a White Supremacist cabal supported by millions of terrified, xenophobic enablers, resisted by millions more and still an ongoing hostage situation for still millions more Aboriginals (First Nations people which includes the Spanish-speaking original inhabitants of the settler state's southwest) and Africans.

There is nowhere in the world that is free of human problems. Here on Elephantine Island, home of the original center of Ancient Kemet's trade with inner Africa, we have talked at length with the modern Nubian descendant's of those who maintained and renewed the Kemetic state from what is now the Sudan and Ethiopia. They face racism here in ways both familiar and unfamiliar to their cousins in the United States. As Du Bois once wrote, "the color line belts the world."

With a moleskine full of jotted notes, I'll be posting more thoughts on the days we have been here in the days ahead. In the interim, I've been reading through some of my blog posts from previous journeys. We initiated Howard's Summer Study Abroad in Kemet in 2008, the year after Asa G. Hillard III (Nana Baffour Amankwatia II) made transition here in the Nile Valley during our Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations conference. We have returned many times since, and will continue this journey annually. We are part of a genealogy and a practice that demands it. One that Asa, Yosef ben Jochannan, Jacob Carruthers, William Leo Hansberry, Alain Locke and so many others undertook, inherited and renewed. We will not be the weak link in the chain, one that extends backward to far antiquity and forward to our complete liberation.

Below is a post from 2009 and the second Study Abroad Kemet journey. The students who travelled that year are now professors, lawyers, farmers, community activists and many other things besides. The fullness of our collective efforts has not been communicated. Coming back to the deteriorating racial politics of a re-forming settler state, we have a renewed purpose. Part of that purpose is to remind ourselves that we work to create the world we wish to live in.

[Aswan, Upper Kemet, Sunday, August 9, 2009]: As our bus hurtled back toward Elephantine Island and the hotel Saturday afternoon, we still had miles (kilometers here) to go before we slept, though we had met a 2:30 a.m. wake up call and departed by ferry for the bus caravan to Abu Simbel at 3:30 a.m. Since the beginning of our journey, and without sacrificing punctuality, we have emancipated time from the tyranny of the clock, and are the better for it intellectually and emotionally. Who has classes, after all, on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights after a dozen hours spent travelling to, climbing into, through, over and around ancient temples and tombs in African summer weather? We do, it seems.

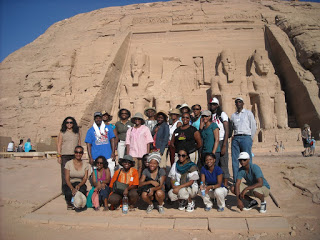

Abu Simbel. Barely twenty miles from the border between Egypt and the Sudan. Ramses IIs’s single most impressive monument: two temples, one to the primary Netcher of his era, Amun Ra, and the other built on behalf of his wife, Nefertari, to the glory of Het-Heru. A love story set in stone, and at once a commentary on how to unify a state around a single shared idea: the Great House. In the wake of the 40 year old Black Power/Black Studies movement and the study tours of Egypt by African-Americans that it sparked, the country should have by now rendered the sight of two dozen Black folk with cameras, pens, pads and studious expressions commonplace. Still, we arrest the attention of tourists and temple guards alike.

Ramses has emerged, with The Memphite Theology, as a particularly helpful subject informing our consideration of “The Politics of Translation” and “The Challenge of Intellectual Integrity.” Friday night we spent a spirited class session examining the parallels between the account of Ramses’s struggle with the Hittites and their allies during the epic Battle of Kadesh and Christian allegory in the Bible. The uber-Pharaoh is frequently saddled with the speculative label of being “The Pharaoh of the Exodus.” If there was an Exodus and if it happened under Ramses, all the more evidence that the Abrahammic religions are extended riffs on a Kemetic melody. As we read passages from Ramses’s plea to his father Amun to assist him and examined his dogged reproaches for seemingly being abandoned, the light in several students’ eyes shone: it was, after all, the Gethsemane and Golgotha pleas of Christ, two thousand years before, not to mention David and Goliath, Joshua at Jericho and Gideon, just for starters.

Howard University Study Abroad Kemet, Abu Simbel, 2009

The next day, we stood in the innermost chamber ofthe temple, (called the “holy of holies”). This chamber is the inspiration for the pulpits that mark the sacred center of churches around the world. There are no guides allowed in the temple: in peak season (October through February), the thousands of people visiting daily would make the presence of guides in each temple proffering detailed explanations literally impossible. Still, we manage to discuss the most important scenes on the walls, columns and ceilings while absorbing the impatient urging-ons of the patrolling police and temple guards.

Nijel and Angi at the Nubian Museum.

Having finished examining Ramses’s temple, we moved quickly to the temple for Het-Heru (the Greek Hathor) built for Nefertari (Ramses's temple is on the right, Nefertari's on the left). We entered, examining an exquisite relief of Ramses in battle, with Heru arming him with a mace of strength and, behind him, Nefertari, arms raised in protection, giving him something to return home to after fighting. The unifying concept of the Per-Uah restoring Ma’at has emerged as a constant theme as well, appearing in the well-documented efforts of Piankhy, Shabaka and Taharqua mounted at the Nubian Museum of Aswan, which actually allows visitors to get "up close and personal" with the classical artifacts.

Angi, Brittany and Robert with Shabaka and Taharqa, Nubian Pharaohs of the 25th Kemetic Dynasty, Nubian Museum, Aswan

There are two reliefs in the back chamber of Nefertari’s temple, opposite the walls that framed her holy of holies. To the left, Ramses II worships his wife, with lotus flowers and Het-Heru behind him, sistrum in hand, coaching and urging him on. On the right, one of my favorite scenes, Het-Heru and Auset flanking Nefertari, breathing life into her. The royal epithet at the top of the first column of Mdw Ntr above Nefertari’s head, “Hemetch Nsw,” [King’s Wife]. The determinative for wife is a well full of water, the single most important element of creation and the thing that a human being—and a man needing a wife—cannot live without.

Friday morning, we had stood astride the Nile’s life-giving water on the bridge overlooking the Aswan High Dam. Looking downriver toward Abydos, Memphis, Saqqara and the Giza Plateau, we were reminded of the majesty and beauty of the land that thirty centuries of Black women and men had come together to create and share with the world. We surveyed the dry granite outcroppings that form the Nile’s final and northernmost of its six cataracts. Seized by the need for a mnemonic unguent, I scrolled through my Ipod’s playlist for a sufficiently powerful performance to lash the moment fast against the hard backbone of my mind’s long-term memory.

My eyes widened as the thumbwheel alit upon an Ancestral choice. I imagined Amenemhat, Ahmose, Hatchepsut, Piankhy and Ramses standing astride, along and upon the Nile, looking down the expanses of time and space and envisioning their successful efforts to realize Sma Tawi, Nsw Bity and Neb Tawi, the United Two Lands. As the dulcet harmonies of Lauryn Hill eased through my ears, the sudden turntable scratch emptied into the existential question that our children raise in the wake of perpetual challenges to their potential and doubts about their abilities, a question that evaporates when raised against the memory and vision of Kemetic serenity, permanence and relentless, unceasing movement: “Life…I wonder…Will it take me under?”

For fully three minutes, an eternity in hip hop timespace, I stood, motionless, before the Nile and the memory of the great African past, allowing Nasir Jones to resolve the seeming hopelessness of a puny and contemporary racescape against a hungry if as-yet underfed vision of what will and must be as he opined what he would do “If I Ruled the World.” His words and Lauryn’s melody catalyzed a comingling and bonding with my own mind’s eye as it played images of Pharaonic command and mass public effort, teeming all along the river’s four-thousand mile expanse over the three millennia of Kemet’s unbroken command.

“If I ruled the word/I’d free all my sons/Black diamonds and pearls/If I ruled the world…”

Our band seeps with contemplative deliberateness out of the busses and takes in each new site’s wonder: the steppes that frame the Tombs of the Nobles on Awsan’s west bank, including the tomb of Hardjuf, known as “the world’s first explorer” for his survey of inner Africa; the mirth of children in an Elephantine Island village that has been adopted by wave after wave of African-American visitors.

“Open they eyes to the lies/history’s told foul/but I’m as wise as the old owl/plus the gold child/seein things like I was controllin’/clique rollin’/truggers six digits on kicks and still holdin’/trips to Paris/I civilized every savage/give me one shot/I’ll turn trife life to lavish/political prisoners set free/stress free/no work release/purple jet skis/and M 3s…”

Saturday morning, as our little boat neared the island where the Philae Temple of Auset (Isis) has been preserved, we scanned the cliffs and foliage for the white birds whose craning necks indicated that we were looking at the descendants of Djehuty. The egret, of the ibis family were further proof that the people of Kemet were Africans. The symbols for intellectual work: the noble and silent baboon and the elegant, aloof ibis—were animals found only inside Africa, deeply beyond the reach or influence of Europe. The temple, built during the Late Period of Greek and Roman authority by Kemetic architects and designers, became the last temple where Kemetic spiritual systems were openly observed, by the Nubians. It was closed by the Roman Emperor Justinian, but not before Auset had transformed into Mary and written the “Cult of the Black Virgin” on the religious DNA of Christianity, from the re-inscribed portraits of Madonna and Child to the re-inscription of the largest single shrine to Isis in Western Europe to the Cathedral of Notre Dame (Our Lady) in Paris.

In the U.S., we have battled against the dim and vacant gaze of absence in the eyes and souls of children who have been pulled away from the excellent practice of study by distractions, real and imagined. As my mind’s eye framed image after image of our students drinking in inextricable sets of life-altering images, Nas and Lauryn’s declaration evoked the answer to the seemingly intractable question, “why?” They do not do better because they do not know. They have not seen. And, after all, we need not question what we would do if we ruled the world. In fact, the lessons of Kemet remind us that we rule the worlds our imagination and deliberate, excellent effort allow us to create.

Catherine Carr and Sawdayah Brownlee with a New Kingdom Scribe at the Nubian Museum, Aswan. Elder Mother Carr took the journey as a gift from her family to celebrate her 80th birth year, and accompanied by her daughter, Gussie, named for her mother's mother. Her grandson, Ellington Fuller, Gussie's son, completed his first journey to Africa and to Kemet with HU Study Abroad Kemet in 2018.